According to Bloomberg, electric scooter mania is taking over cities. CityLab dubbed 2018 the “Year of the Scooter.” And from Providence, RI to Portland, OR e-scooter pilots have been popping up seemingly daily.

But in the face of the e-scooter boom, what’s going on with bikesharing—the original micromobility? How are bikeshare systems evolving with changing demand? In a multimodal network, will the modes complement each other, or compete, or some of both? Below are five major trends SUMC sees as emerging in the bikeshare market in 2019.

While dockless bike systems in smaller markets have largely been replaced by e-scooters, many of the largest docked systems are benefitting from greater investments and network expansion

While some cities, like Seattle and Orlando, are still home to dockless bikeshare systems or markets, many dockless operators have shifted their attention to e-scooters, which appeal to providers because they’re cheaper to manufacture and easier to rebalance. For example, Lime (which tellingly dropped the “Bike” from its name in mid-2018) pulled its green dockless bikes off the streets in a number of markets in early 2019 in favor of their e-scooter fleets. This left several cities, including St. Louis and Rockford, IL, without a bikeshare program at all.

Despite this shift away from dockless bikes to e-scooters, cities with large docked bike programs are leaning into their established systems. For example, New York’s Citi Bike announced this summer that it plans to nearly quadruple its existing 12,000-bike fleet to 40,000 bikes and double its coverage by 2023, including large expansions into the Bronx and Queens. Similarly, Chicago’s docked system is expanding to all 50 of the city’s wards in the next three years, and the DC region’s Capital Bikeshare added a seventh local jurisdiction to its system in May 2019.

However, while the docked systems in America’s largest cities are expanding, it remains unclear if the trend will be mirrored in smaller cities. Because of the large capital investment required for a widespread docked system, it is possible that dockless bikes—or perhaps the popular e-scooters—will emerge as the option best suited for smaller markets. Another possibility is that more cities will follow the lead of the Twin Cities’ Nice Ride MN and pursue hybrid bikeshare systems, using both physical and virtual docks, with the system becoming increasingly dockless as equipment reaches the end of its life cycle.

E-bikes and adaptive bikes are on the upswing

Many systems are also expanding the types of bikes they offer. Bikeshare operating giant Motivate (acquired by Lyft in 2018) has promised to incorporate e-bikes in its markets, and already began to roll out a new generation of hybrid e-bikes despite recalling over 3,000 e-bikes in April 2019 due to safety concerns. The company has made it clear that it envisions transitioning much of its existing fleets to e-bikes in the coming years.

Similarly, the fleets of the vendors participating in Seattle’s dockless bikeshare pilot (Jump, Lime, and Lyft) consist entirely of e-bikes. They are overwhelmingly popular, particularly among commuters who want to bike to work without showing up sweaty, as the electric motor helps riders travel with less effort. In hilly areas like Puget Sound, the electric assist also makes biking a more viable choice for all kinds of trips for travelers at a variety of fitness levels. In cities like Madison, WI, and Fort Worth, TX, that have added e-bikes to their fleets in recent months, ridership has increased significantly.

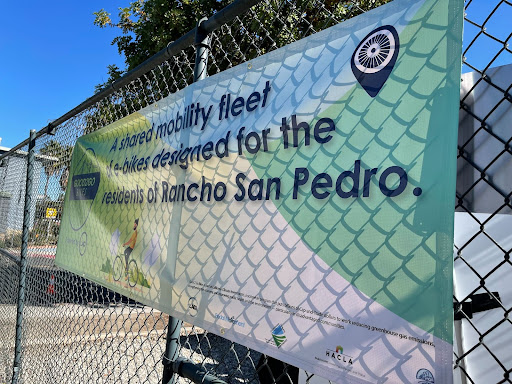

The disabled community has also successfully pushed for bikeshare systems to incorporate adaptive bikes. These bikes, which include hand-powered, easy-balance, and tandem, help people with physical limitations take part in local bikeshare systems. Detroit , Oakland, and Portland have already launched adaptive programs, and Chicago’s new agreement with Lyft/Motivate requires that the operator incorporate an adaptive program within the next few years.

Bikeshare is becoming more deeply embedded in communities

Across the country, cities are integrating bikeshare with existing transit services, reinforcing bikesharing’s role as part of the public transit system. Portland, OR, now allows individuals to purchase a bundled “transportation wallet” that provides transit passes and bikeshare access at a steep discount versus purchasing the services separately. Pittsburgh is encouraging residents to use bikeshare to connect to transit trips by offering 15 minutes of free bikeshare for transit riders. Residents can simply use their public transit farecard to unlock a bike from the local “Healthy Ride” system.

Another trend revolves around markets typically not courted by bikeshare operators. Small and rural communities’ lower population density often makes implementing a fiscally sustainable microtransit program significantly more challenging. Because these smaller communities have different mobility needs and resources at their disposal, they are establishing their own bikeshare systems. Towns such as Pocahontas, IA, and Brusly, LA, are finding that, by owning and operating their own small fleets of shared bikes (instead of contracting operations out to a more expensive private party), they too can offer their residents bikeshare as a mobility option.

Markets are defining different operational models for different types of communities

When launching a bikeshare program, cities must consider local conditions and community needs, including density, geography and weather, potential bikeshare ridership, and infrastructure to support safe biking in general. However, the most central question for most cities is: how should we manage our bikeshare system? Should we select a single vendor or issue permits to multiple vendors, and how much are we willing to invest ourselves? Patterns are emerging that suggest that certain system models are better suited to certain community types.

Public-private partnership (P3): Some of the largest bikeshare systems in the U.S. are managed by a P3, where city departments (which can access different funding and financing sources than private companies) can share the burden of the significant up-front capital investment needed to launch a large-scale system. With a designated P3, the city has committed private sector involvement, and the selected operator can utilize their private-sector expertise while leveraging support from the supervising public agency. Cities like New York City and Chicago use the P3 model for their docked systems. These systems often benefit from advertising and sponsorships to further offset public costs and user fees.

Privately owned and operated: A private model can be one in which a city grants one vendor an exclusive right to operate in a community, or it can be one in which the city grants an operating permit to one or multiple qualifying vendors. With a permit model, a city allows a dockless bicycle provider to operate on their streets, charging companies a per-bike or annual fee (or both) and setting guidelines on where and how vendors can operate. The benefit of such a model is that there is no investment required on the part of the city beyond the cost of administering the program; the risk, however, is that the city has no commitment from operators to remain in the market, as communities like Saint Louis, Saint Paul, and many others experienced when Lime withdrew its bikes.

While the crest of the dockless wave has passed, and many dockless bikeshare operations have given way to e-scooters, a few cities with a strong biking market (such as in Seattle) have kept their dockless programs. For most cities, however, some degree of investment—such as in branding and geocoding traditional bike racks or parking zones—may be needed to support a permitted dockless or hybrid bikeshare operator going forward. Exclusively issuing permits for operation without any city investment has primarily become the domain of e-scooters.

Interestingly, some cities (such as Washington D.C., New York City and Chicago) have experimented with permitting private dockless programs to operate in conjunction with their public docked systems, but as a 2019 lawsuit in San Francisco can attest, this can be a tricky endeavor.

Non-profits: It is increasingly common among bikeshare systems for a local non-profit to “own” the system. In cities like Denver, CO and Philadelphia, PA, a non-profit contracts with a private operator to manage the bikeshare system. Because the bikeshare is not a city program, the city does not have to invest capital, but neither does it receive any revenue from the program. In most cases, the city does provide subsidies or sponsorships. The risk with such a model is that the program’s funding relies on grants and gifts. Nevertheless, it is used across the country for systems of all sizes, and for both docked and dockless bike programs.

City-operated leased bikes: This emerging model is one used almost exclusively by small and rural communities. For example, the Iowa-based company Koloni works specifically with small towns to bring city-owned bikeshare systems to them. In these markets, the city—not the company—is responsible for operating the bikeshare system; Koloni rents the bikes to the city for a monthly fee, which also includes use of the online platform for locating and paying for bikes. This model is typically used for very small dockless or hybrid systems, since the smaller communities willing to balance and repair their own fleets are rarely interested in investing the capital needed for a docked system.

Feds are starting to catch up to bikeshare’s benefits

As bikeshare grows in value around the country, many communities’ members of Congress have taken greater steps to support it. A House bill introduced in July would make some federal transit funds available to bikeshare programs, a huge step in recognizing bikeshare as an important and valid component of a transportation network. Another Senate bill would require that 5% of each state’s Federal highway funds be allocated to complete streets programs, which would support construction of biking infrastructure. And the $287 billion federal transportation bill released in July, 2019 includes an increase in funding for “Transportation Alternatives” such as biking and walking.

Overall, safe, well-designed infrastructure is key to micromobility use, and this will require expanding or remaking existing paths, roadways, and facilities. Hopefully, more federal legislators will learn to consider biking and walking (and scooting) forms of transportation in themselves, not an “alternative,” so needed investments can be made.

__________

What do these trends indicate? While the hype surrounding scooters may suggest they are the mode of the future, expansions in bikeshare system coverage, the integration of payment options with public transit, and the roll out of electric and adaptive bikes suggest that bikeshare continues to be seen as an important component of any city’s suite of mobility options.

Mobility trends come and go, but SUMC believes that both modes can work together as part of a multimodal network of accessible, affordable, and environmentally sound transportation options. If these trends continue, bikeshare will grow even more deeply embedded in communities and transportation systems in the years to come.