What’s rechargeable, fits in your pocket and can help you leap tall hills in a single bound? A personal, electric bikesharing battery, of course.

One of the next big potential trends in urban transportation, electric bikesharing can help expand mobility and increase bike use by offsetting barriers like hills, heat and urban sprawl that make cycling difficult. In 2015, Birmingham, Alabama launched the first city-scale bikesharing system in the U.S. featuring e-bikes, and other cities such as Seattle and San Francisco have also expressed an interest in electrifying their fleets.

While some European bikesharing systems are already powered by electric bikes, the concept has yet to fully take hold in the U.S. E-bikes tend to be a little heavier, more expensive and unfamiliar to American riders. Additionally, bikeshare stations have been traditionally been freestanding, solar-powered pods that can be deployed relatively quickly. To charge electric bikes, however, most stations will need to be connected to the city’s power grid, requiring construction permits, digging, inter-agency coordination and other complications (Ed. Note: Birmingham’s Zyp system is solar powered).

Now, outdoor advertising magnate and bikeshare operator JCDecaux thinks it has come up with a possible workaround: a personal, rechargeable electric bikesharing battery that can turn a regular bikeshare bike into an e-bike. The company unveiled its new solution at the Paris Climate Conference last November, where the demonstration turned some heads…and raised a few eyebrows. Will JCDecaux’s gambit work? As the French say, “Qui vivra verra” (he who lives, shall see).

“Bring Your Own Battery”

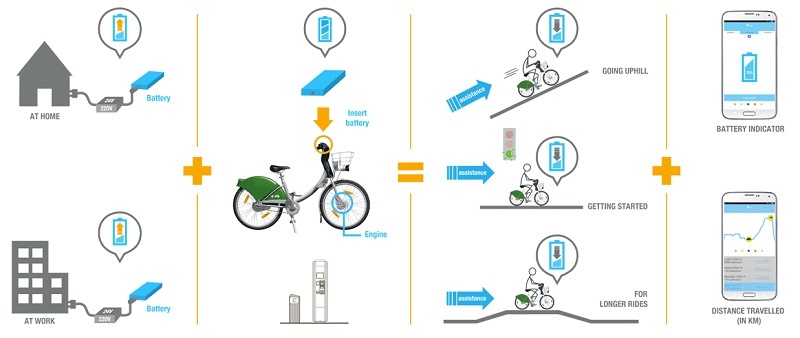

JCDecaux’s “bring your own battery” concept, officially called e-vls, revolves around a relatively light, 1.1-pound detachable battery that’s about the size of a paperback novel. The battery has enough juice to provide an electric pedal assist for a distance of up to 10 km (about 6 miles) at a maximum speed of 25 km per hour. As a benchmark, the average trip on Paris’s Velib bikeshare system is about 2.5 km, which suggests maintaining the bike’s charge during rides should not be an issue. And, according to JCDecaux, it only takes about an hour to fully charge the battery, which can be done at nominal cost.

While each city would need to determine how to best roll out the tech to its bikesharing members, JCDecaux envisions mailing batteries and chargers to users. Cities could also explore the idea of partnering with local retailers, where users could go to retrieve their equipment. For example, in Paris, the company suggests it could use the city’s network of newspaper stands as a possible solution.

Once members receive their battery, they would just need to charge it at home or work before heading out the door, then pop it into a slot between their bikeshare bike’s handlebars, turning a regular bike into an e-bike courtesy of a front-wheel pedal assist motor.

Additionally, JCDecaux’s e-vls system connects to a smartphone app, which can help riders track the distance they’ve traveled and monitor the remaining charge on their battery. And, for those forgetful types, the bikes also come with an automatic warning to alert riders who attempt to walk away without removing their battery.

What it Means for Cities

While the “BYOB” concept is a little unorthodox, it does offer several appealing aspects for cities. One is the ease of accommodating the new technology. Since the bikes will not need to be charged while docked, cities won’t need to worry about the hassle or expense of connecting stations to the electrical grid. In fact, existing JCDecaux partners – which include Paris, Vienna and nearly 70 other cities worldwide – will be able to integrate the e-vls bikes into their existing system infrastructure, meaning this new concept can be deployed quickly in cities without service interruption.

The bikes themselves will also change very little. Although they will be fitted to accommodate pedal-assist motors, they will look and feel like traditional bikeshare bikes. And riders can continue to use them without batteries if they choose.

“This is at the heart of JCDecaux’s e-bike sharing concept,” said company spokesperson Guillaume Aper. “Users are free to choose whether they want to ride electrically or not…People who choose not to have the battery will still be able to enjoy our bikesharing systems. It’s the same bike. It simply benefits from electric assistance if a user inserts his or her battery.”

By not forcing cities to hit the reset button on existing systems, JCDecaux’s concept could help electric bikesharing expand more quickly, especially in cities with hills or other geographic challenges. And, just as bikesharing has shown itself to be a “gateway drug” to cycling, electric bikesharing can help encourage greater e-bike adoption, which could have important implications for mobility. With their pedal assist technology, e-bikes can help people cycle further and more frequently, making bikes – which are already competitive with cars for short urban trips of 2-3 miles – a viable option for even more types of travel.

“It really increases the range of how far people can bike, and how likely they are to bike, especially in a hilly city,” said Nicole Freedman, president of the North American Bike Share Association (NABSA). “If you take someone who hasn’t biked in years and put them on an e-bike, it’s amazing. It really does attract people who would not be biking on a standard bike.”

For all its promise, however, JCDecaux’s concept has also been met with some skepticism.

“I can’t imagine the people who are in the market for bikeshare that requires you to carry your own batteries,” said Randy Neufeld, director of the SRAM Cycling Fund. “I think it is easier to connect the stations to the grid or have service vehicles swap the batteries. The next step is e-bikes shared in fleets.”

Critics have also suggested that the design’s front-wheel motor might not be ideal for bike handling and safety, although Freedman notes opinions on power assist vary widely within the industry. Meanwhile, others are more optimistic.

“If the concept works well in Paris, it may have a lot of appeal for U.S. systems that desire the e-assist feature but have big investments in solar-powered station networks,” said Jon Orcutt, a spokesperson for TransitCenter who previously oversaw implementation the CitiBike bikeshare system for the New York City Department of Transportation.

NABSA’s Freedman agrees. “I would think designing an entire system for electric is the better solution if you’re starting from scratch, but my instinct is that if you’ve already invested a lot in an existing system and want to go electric, you might consider a battery swap system,” said Freedman. “In this phase, when you’re talking about new equipment and technology, it’s always good to keep an open mind.”

While JCDecaux says its e-vls concept is fully operational and will be marketed worldwide, it’s still unclear whether it will be the electric bikesharing solution that cities need. Still, there’s no doubting its innovative nature, and SUMC looks forward to following its progress. After all, sometimes it’s truly not possible to pass judgement on a new approach until you take a chance and move forward with pilot testing. Or, to quote another French proverb – “En cas de doute, gallop!” (When in doubt, gallop!).

For more on electric bikesharing, check out SUMC’s recent piece “Could Electric Bikesharing Be the Car-Killer America’s Been Waiting For?” And, be sure to sign up for SUMC’s regular newsletter to keep up to date on the latest developments in bikesharing, carsharing, ridesourcing and more.

Images courtesy of JCDecaux